Corporate Sludge Motivates SF Activist to Action

|

|

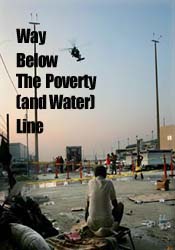

by James Chionsini/STREET SHEET As I watched people dying on national television in the days following the Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent levee breakage, I realized that the problems were far larger than the storm itself or the government’s absolute failure to respond effectively. The people left behind were living in abject financial poverty, too poor to get out of town, too poor to warrant proper upkeep of the levees that protected them, too poor to be worthy of rescue by a system that had built its wealth on their backs. With the military busy making the world safe for oil companies by killing poor people overseas, there weren’t even enough troops left at home to save seniors from rooftops. I chose to volunteer with the Red Cross (not the band), because they paid for airfare, lodging and expenses. I signed up, took a one-day training and found out I could be called at any time in the next few weeks to be deployed within 48 hours. One month later, my cell phone rang. I kissed my pregnant wife, Sarah Beth, and our 4 year old son, Day, goodbye and on Thursday October 6 left for Baton Rouge. I am fortunate to have a job at the Coalition on Homelessness that allowed me to go to Louisiana for ten days and still pay me for those days. I took a bundle of the October Streetsheet and promised to engage in outreach and report back. This job kicks ass sometimes. Flying American Airlines seated in the first class cabin, I struck up a conversation with my neighbor, a fertility doctor from Dallas. He told me about a wealthy White patient of his from New Orleans who escaped the city with her family in their fleet of Mercedes prior to Katrina”s landfall. She was staying in luxury hotels, waiting to return. He reported that she commented on the people trapped in the Superdome, “They ought to just drop a bomb on the place, that would save a lot of money and trouble.” We agreed that racism was doubtlessly at the core of her sentiments and that her cruel words reflect attitudes held by many in this country. I felt nauseated as the flight bounced through the dense, white Texas cumulus clouds. This is what we are up against. At the Baton Rouge airport I found the Red Cross representatives; a friendly but weary group of seniors wearing Red Cross vests and plastic photo nametags. An older African-American man who had lost his New Orleans home to the rising waters from the breach of the 17th street levee drove 10 of us to the “staff shelter.” He was surprisingly upbeat and talkative considering his circumstances, saying, “Me and my wife survived. We lost everything but ourselves. I consider myself lucky so that”s why I joined up to volunteer with this outfit.” One of Many Shelters The shelter was in a recreation center office next to the public swimming pool. I claimed a cot and proceeded to get to know my neighbors. The one sporting an American flag hat was a retired parole officer from rural Montana with a son in Iraq. Then there was the bearish Gay Black Anarchist from Baltimore, who as it turned out had always wanted to live in San Francisco. Yet another was a Methodist minister from Cleveland who boasted about the type of cocktails he enjoyed and the size of his former congregation. I stayed up late in the night eating Pop Tarts, smoking menthols and chatting with the local security guards, one of whom used to play in the rec. center playground as a child. The population of Baton Rouge has doubled since the storm and the influx of evacuees. “Y”all watch out for snakes out there in that field.” she warned me. “What about alligators?” “Not here in town.” Early the next morning a Swamp/Plantation tour bus with a lime-green alligator painted on the side transported us to a vacant Wal-Mart that had been pressed into service as the Red Cross headquarters in Baton Rouge. Smokers lounged behind the fenced-in former Lawn and Garden Center, languidly watching the new volunteers arrive. Some there were waiting to be deployed (some reported waiting two or more days), others were awaiting redeployment or on their way home. I was issued a photo name card and assigned to “feeding and shelter” but no one had any idea where I would be sent. I activated my credit card, ate several free “Honey Buns” and other tasty junk food items, and waited to be told where I would go. They were from all parts of the country and from a pleasant and remarkably harmonious diversity of political persuasions. All of the volunteers I met seemed like really kind spirits. Lots of chatting. Hella church people. Nine hours later five others and I were transported to Covington, Louisiana, site of another Red Cross “headquarters.” Outside the Covington office I noticed a man wearing the stereotypical black-and-white striped prisoner uniform. He was a county jail trustee assigned to maintenance of the building. “I been in six months, rode the storm out here in jail, getting out soon, I”m from New Orleans but my house is gone. Took in about 8 feet of water. They let me go see it with my brother-in-law. The house is ruined, covered with mud, it”s all ruined.” He told me about some people in New Orleans jails who were not evacuated and drowned in their cells. “I guess I”m lucky compared to them.” Destination: Hammond Our party was ultimately sent to Hammond Louisiana, a small college town 45 miles east of Baton Rouge. We were housed in a Presbyterian church that had been designated as “staff shelter” and informed of our responsibilities: working with the evacuees housed in two nearby “client shelters,” both in Baptist Churches: Mount Vernon and Emanuel. We visited Mount Vernon and talked with the “shelter manager.” He was a former Coast Guard member from Detroit who claimed to have experience with “law enforcement.” FEMA was bringing in trailer to accommodate the evacuees. There was a lot of miscommunication and confusion about when and where people would be sent. “Things change daily, and there are problems with these people here, they don”t want to leave,” he said. There were seven National Guard troops with M-16 rifles sitting around looking very bored. They had been called in to replace the Louisiana police that were “protecting” the evacuees. Immanuel Baptist Church in Hammond housed about 150 evacuees from rural Plaquemines (plaque-mans) Parish (counties are called parishes in Louisiana). Plaquemines is the southernmost parish in the state, a slender peninsula that extends like a long toe from the end of the Louisiana boot. It is where the Mississippi River meets the Gulf. It is the beginning and end of the line. Katrina has changed the shape of the marshy shoreline there. Many towns are completely gone; reclaimed by the sea. Of those that survived the houses are nothing but piles of wood and mangled metal. The strange fruit in the trees these days consists of boats. The people of Immanuel shelter had literally lost everything and had nowhere to go. Apparently FEMA was going to provide trailers, but no one, not the people themselves nor the Red Cross knew or would say anything. The temporary shelter was set up in a large gymnasium. Everyone had cots or mattresses, along with all their personal possessions in areas arranged like a series of small living rooms, without walls. Some folks had couches, televisions and radios and there was a lot of noise and activity as the kids played in the areas of the gym that were clear. My job was working in the kitchen and helping around the shelter. That consisted of smoking with the people outside, trying to make people laugh, holding babies, crisis intervention, playing with the kids and serving food cafeteria style. I had a lot of time to hang out and talk with people. They were a tight knit community, having virtually all grown up together in Plaquemines. Many people never previously ventured outside the parish. Most of the people did not like the city and only went to New Orleans when it was absolutely necessary for doctor”s appointments or business. They were Deep South rural country folks who had grown up in moderate to extreme poverty. Out of 150, all were African-American except for two older White men, one of whom was Deaf. What struck me was the remarkable stability and mental health of the people. There was a definite depressed mood, but most people seemed to be in relatively good spirits, even the kids. There was one 10 year old out of the 40 some odd kids who showed visible signs of distress. In the middle of a kickball game he ran to me crying, hugged me around the chest and pointed at a snarky teenager near third base, “He told me to run home, and I got out. He told me to run home. I want to go home, where is my home?” The others seemed to understand, got real sad and we all took a break. They consoled their friend with playful jabs. The game quickly diverted to playful child energy chaos. A huge dumpster nearby overflowed with abandoned and broken furniture. The six National Guard troops who were stationed at the far edge of the church parking lot were in their early 20”s had just returned from a year in Iraq and were really disgusted. The sergeant told me, “We are engineers. We drive bulldozers and can tear down and build shit. Why the fuck are we sitting around here when we could be helping clean up the god damn mess all over this state? There are some serious problems going on around here. I don”t know why they have us guarding this place. FEMA is fucked up!” The soldiers were actually really cool people. Total working class dogs from Maine. “Are you all going to get sent back to Iraq?” I asked them. “Don’t know, but I hope not,” was the general consensus. “I wanna go back. I”ve already put in my request,” said a visibly anxious young soldier with Elvis sunglasses. “Be careful over there cousin,” I told him and held up my hand high-five style to shake his. He flinched and spilled hot coffee all over his arm. “Yeah yeah. I will I will. Thanks man,” he stammered. Two days later at around 4 pm one of the soldiers accidentally discharged his M-16 in the parking lot. The bullet ricocheted off the ground and knocked out a car window three blocks away. That entire crew was replaced the next day by two local women with the Louisiana National Guard. We all got a big kick out of laughing at the lemon-size crater in the asphalt. “Those guys will be cleaning toilets for 3 months,” one of the soldiers told me. They shared the same sentiments as the previous soldiers. “We have all this equipment just sitting there not being used. Why? It’s a damn shame.” I talked at length with one man from who had worked for 20 years as a “sucker” on a fishing boat. He would go into the hull and suck the fish from the nets out with a big hose The fishing industry in Plaquemines is almost totally wiped out since Katrina and Rita. He talked somberly about his experiences. “Cars like those over there just sliding sideways across the road. Whole trees ripped right out of cement and thrown through the air. Houses had their roofs blown off. Water coming in everywhere.” He and some family members had evacuated to New Orleans before the storm and had gotten trapped there when the levees broke. “We walked five blocks in waist deep water only to get somewhere to be told there wasn’t any busses and were sent off three blocks away in chest deep water. We were sitting on top of cars and anything we could find. It was horrible and I was scared. I’m still scared man, I don’t know what the hell is going to happen to me. It’s all gone.” He said FEMA hadn’t done anything for anyone at the shelter, “They showed up once, took some names then never came back again.” Everyone had stories like this. It was difficult opening that can of worms. People don’t want to be reminded of horrific situations so soon after they happened. People were really willing to talk though. I explored the topic of life before the storm. People cheered up. There were people from small towns named Point-a-LaHache (poine la hash) , Belle Chasse (bell shays), Port Sulfur (poat sailfur), Buras, Bohemia, Dalcour (dakur) and Naomi. The population of the entire county was only 26,000. The industry was primarily fishing, chemical plants and shipping electric coal that came down the Mississippi headed for Florida. People took seasonal jobs that varied throughout the year. They said there was very little crime, doors were left open. “If anyone was to ever steal anything from you, you would know who it is or someone would tell you. Kids ran around without shoes, we was one big family. We were poor but we had each other, still do,” one man told me. “You could always get oysters, shrimp and fish. And it was always cheap. Friends would just bring you a sack or two and you didn”t even have to ask. Now my mobile home is totally gone and my boat is 20 feet up in the air in a tree!” He and everyone I spoke with planned to return and rebuild. “Home is Home” they all agreed. I gave out copies of October Streetsheet and this helped me gain the confidence of the people there. They liked the story, “The Drowning of New Orleans,” and figured I must be ok if I am handing out material such as this. People were interested and supportive of the Coalition on Homelessness. When asked if anyone in their group had lost their mind people laughed, “There has been a whole lot of crying, but we are all together and even though we are staying in a gym, you always got a shoulder to lean on,” a 68 year old man from Point-a-LaHache told me. There was enough mutual support to go around. Poverty: the Real Disaster Before Katrina (and Rita), Louisiana had by far the highest unemployment rate of any state (11.5%), and in some areas, as high as 25%. It has adult illiteracy rates of 28% (second only to Mississippi with 30%). Racism and exploitation are also alive and well in the South. Over 13% of children in Louisiana live in extreme poverty that is, in families with an income less than half of the federal poverty level, or $9,675 for a family of four compared to a national average of 7%. These children are disproportionately African American. In Louisiana, 44% of black children live in poor families, while 9% of white children live in poor families. (Source: National Center for Children in Poverty. http://www.nccp.org/pub_cpt05a.html) The Red Cross is designed to provide temporary, emergency food and shelter for a few days at the longest. It is a very different matter to provide emergency services to people whose homes in Walnut Creek have burned down than to try to help those in the Deep South who can not read and have never traveled more than 100 miles from their homes. The magnitude of destruction caused by Katrina and the 20 something percent % of people living in poverty with few options has presented problems that the Red Cross is simply not equipped to deal with. The Red Cross mantra is provision of “temporary shelter and housing” and it is not equipped to address historic patterns of structural poverty. In Louisiana and Mississippi at this time are thousands of extremely poor people who have suddenly become homeless. All over the South, people are being warehoused in hotels, stadiums and auditoriums because there are no places for them to live. The Red Cross is attempting to discharge people, often with very little follow up or consideration of special needs. Evacuees are being shipped out of state with 30 day hotel vouchers, but when that money is gone, they are on their own. The maximum amount someone with a family of five can receive from the Red Cross is $1565. That doesn’t last very long and unless they are fortunate enough to get a trailer, they are out of luck. Civil Disobedience Against FEMA (Failure to Evaluate Meaningful Alternatives) FEMA employees arrived at the Emanuel shelter, claiming they were providing trailers that people could move into. At the request of the residents I asked the FEMA representatives about the location, and they informed me there was a school and a store nearby and the place was really hospitable. Most of the residents were dubious, but a few families took up the offer and were transported to “Mount Herman.” We received a frantic phone call a few hours later from those who had left: The place was horrible and the evacuees were refusing to stay there. The Red Cross directed us not to readmit these three families to the shelter and to have the National Guard troops prevent the families from entering if they tried to return. Our volunteer team unanimously decided to disobey this ridiculous order, tactfully neglecting to inform the armed National Guard. We spoke to the bus driver by phone and told him to return immediately with the families. A technical error in the paperwork meant that they were not actually officially discharged, so we were covered. Nonetheless, we had all prepared ourselves to be sent home (or worse) by the authorities. The FEMA officials (the same ones that had lied to me) were trying to coerce the people to stay there by saying that if they refused, FEMA would disqualify the evacuees from all the benefits to which they are entitled. FEMA ordered the bus driver to leave them there, but luckily he was a man of conscience and put his job on the line by directly refusing. They returned to the Emanuel shelter. The bus arrived and people’s faces showed a mixture of shock and disgust as they exited the bus. We quickly brought their belongings inside and encouraged the returnees to mix in with the crowd. They told us of the site. It was on a farm that raised goats and ostriches, located about five miles down a dusty dirt road from the nearest highway, miles from any town, in the middle of KKK country. Many of the trailers lacked water or electricity, and there was no sign of either the promised store or school. Wreckage from the hurricane was being hauled in on semis to a nearby landfill. “A dump is a dump and I won’t live in one,” one man told me, continuing, “If the dust don’t get you, the scent from the animals will. That place ain’t fit for humans!” The next day the local paper (Hammond Daily Star, October 11, 2005) bore the front page headline “Trailer City Revolt,” and people in the town were irate that FEMA had tried to place all these folks, many of them children and frail elders, in such a remote and dangerous location. It created a local scandal. The people were encouraged by this writer (not that it was necessary, for they were all in agreement) to collectively refuse to leave the shelter unless adequate facilities were provided. The people agreed that they would not leave unless trailers in a place where the children could stay in school and the seniors could access medical care were found. The FEMA public relations department could have ended up spending a sizable chunk of revenue to explain how National Guard was used to force them from the church shelter. The feeling of solidarity was exciting. The evacuees said, “Hell no we wont go!” The very next day FEMA announced that a location near town had suddenly been “found.” The kids could stay in school in Hammond, and the entire community could stay together. People began relocating to the 3 and 4 bedroom trailers where they could live for 18 months. The evacuees of Plaquemines parish exerted their collective will and won! Everyone was pleased with the trailers, which were fully furnished and livable. The people scored big time. VICTORY! Common Ground Two Red Cross volunteers (a Social Worker from Boston and an archaeology student from LA) and I took a road trip one day in a brand new blue PT Cruiser courtesy of the Red Cross. Gulfport Mississippi (ground zero of Katrina) looked like a nuclear bomb had gone off in the town. Huge brick buildings were reduced to skeletal masses of iron girders. In Slidell, Louisiana, vast mounds of splintered wood (former homes) lined the road for miles. Everywhere, trees were snapped in half and all manner of debris littered the roadways. We visited the Common Ground Health Collective in Algiers, on the west bank of the Mississippi in the New Orleans area. Housed in an old mosque, Common Ground free medical clinic was established by concerned community members and autonomous volunteer medical personnel from all over the country. Based on principles of mutual aid, its initial goal was to provide free medical and humanitarian relief, but it has evolved into a community center that aims to address the history of abandonment, exploitation and neglect with a dignified and respectful health delivery system. It embodies a radical Free Clinic philosophy by providing medical services in an oppressed neighborhood with the full participation of community members encouraged. Common Ground can boast one of the most multidisciplinary of all teams. There are (categories not mutually exclusive) nurses, doctors, psychiatrists, pharmacists, anarchists, herbalists, acupuncturists, community organizers, journalists, legal representatives, aid workers, proletarian neighborhood members, EMTs, squatters, gutter punks, artists, mechanics, chiropractors, clergy, and so forth involved. A huge sign outside the door reads, “Solidarity Not Charity,” and this statement exemplifies the perspective of those involved. I spoke with people from New Orleans and all over the country there. Everyone volunteered their time to help those who came to the clinic. At first they were treating injuries sustained during and immediately following Katrina but at the time of our visit they were seeing people with chronic, untreated conditions. They serve about 100 patients a day, sometimes more. Many of those showing up have not been seen by a doctor in 20 years. It is a true community clinic in that it incorporates members of the neighborhood as part of its organizational structure and aims to create a new paradigm of health care that incorporates community development and revitalization with health services. Where else can you find medical/Mental health care and Copwatch offered under the same roof? Common Ground wants to become a sustainable collective. There is a serious need for legal assistance. It is also in desperate need of political and financial support. If anyone would like to join a visionary, revolutionary approach to healthcare, please contact Common Ground Collective at: www.commongroundrelief.org or by telephone at (504) 361-9659. Please support them and help spread the word. Immigrant Laborers Doing all the Work Latino migrant workers in large numbers are working in the cleanup operations in New Orleans. The restrictions on hiring undocumented workers have been relaxed during the cleanup operations in Louisiana. Living in squalid conditions, they are doing the most dangerous work at unreliable wages. Fly by night contractors are employing them and are not required to comply with labor regulations or provide access to health care. These imported workers there are expendable, exploitable and the firms that use them are not liable for damages sustained over time. The workers are experiencing all kinds of serious health problems. Some Latino workers who cleaned up the Superdome (there were no African-Americans in the entire crew of several hundred) reported to our team that as they were brought in by bus people lined the street and flipped them the middle finger. Locals are not being hired. It is creating class antagonisms when what is needed is unity and solidarity. Where to from here Poverty and oppression are endemic in Louisiana, the South as a region and the United States as a whole. This storm removed the veil that normally obscures poor people from the hegemonic gaze of middle-class America. Thousands of people who lived in marginalized racial and economic ghettos prior to Katrina were exposed, waiting on their roofs for days while news, army and police helicopters passed overhead, unable or unwilling to rescue them. The imbalanced class structure of America is revealed by a simple look at the demographics of those who were left behind. Can you say people of color? Can you say poor people? To quote one of the psychiatrists involved with the Common Ground Collective, “New Orleans offers an apocalyptic mirror into the completely rotten core of a capitalist society run amok by neocon terrorists...We so need a revolution.” Move it forward! |